Our Thoughts

Unpicking the Emotional Power of Charity Advertising How PrismCEP™ can help brands harness the power of emotion

It’s no secret that advertising that resonates with consumers at an emotional level can have more impact long term. But it can be tricky to get right!

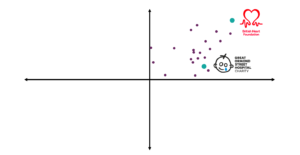

Together with Tapestry, the award-winning quantitative research agency, we’ve conducted an emotional audit of advertising in a category where emotion is particularly important – the charity sector. Using our innovative PrismCEP™ approach to evaluate the communications, we first used the CEP™ Test to measure the emotional power and cognitive power of over 20 recent charity ads, and then used semiotics to decode why these ads work in the way that they do.

What struck our attention straight away was that every single one of these ads sits in the top right-hand quadrant of our CEP™ Test Matrix – they all represent strong emotive power (they can influence consumers feelings through empathy or creativity), but they also have strong cognitive power (they are able to impart new, interest or valuable information). Perhaps unsurprisingly, charity ads are pretty good at tugging on the heartstrings!

But digging deeper, by using semiotics and cultural insight, we’re able to separate the great from the good.

A “Good” Ad: Great Ormond Street Hospital

This ad is fairly classic of the genre, which achieves a good (but not stand-out) score for Emotive Power. The ad follows a standard narrative arc for a charity ad and employs archetypal charity tropes. It starts with emotional stories about young children being diagnosed with life-threatening illness, narrated in the third person by their parents. This is set against a backdrop of slow, sad piano music, with visuals of incapacitated children being aided by adults. Looking away from the camera, and never engaging with the viewer directly, this codes the children as Passive Victims who are in need of help and aid – a key trope in traditional charity conventions that elicits empathy by emphasising helplessness and adversity.

The music then builds into a more positive and optimistic score, accompanied by visuals of a previously disabled boy now playing football and laughing, as the resolution is shared with the viewer: “research is their only cure”. This is a classic narrative arc in the charity genre, which implicitly presents GOSH as a beacon of hope, providing actionable solutions to the problem outlined.

Finally, as this positive resolution pans out, a distant narrator urges the viewer to donate money to help support research conducted by GOSH. Through its distant narration, and its top-down command to donate – rather than actively help – the ad reflects the dominant idea of Expert Authority within the charity sector, where things should be left to professionals who know what’s best. This notion of expertise and authority is reinforced by the medical visuals of uniformed researchers in a lab setting.

Overall, it’s a good ad – it moves people and motivates them to act.

However, what our analysis has shown us is that you don’t have to follow this classic approach to succeed in this space.

Our research has shown that the most successful ads break category norms by using culturally relevant codes in 3 key ways:

1. Firstly, successful ads employ key codes from wider culture that are relevant far beyond the charitable sector.

2. They also show that they’re moving with cultural change, using emergent cultural codes to reflect the shifts that are taking place in wider culture.

3. Finally, they borrow codes from other categories and therefore disrupt the charity sector, making it less likely people will switch off.

A “Great” Ad: British Heart Foundation

This is a great example of an ad that scores really highly on emotive power by breaking category norms, using a key cultural code (Everyday Britishness), as well as an emergent cultural code (Peer-to-Peer Engagement), whilst also borrowing stylistically from the FMCG/CPG category.

The ad centres around a chatty, chubby-cheeked boy with a Northern accent, who speaks in a colloquial style (“and they were like what, and I was like yeah, obviously”) – building empathy by reflecting the lovable rascal character that is so deeply embedded in British culture (think of Just William or Horrid Henry). Crucially, the depiction of this character is also integral to disrupting category norms. In great contrast to GOSH, the boy voices and owns his story of heart disease. Upbeat and able bodied, his chest scars are subtle marks of triumph, rather than of victimhood. The depiction of an Empowered Rascal thus disrupts, engages and surprises an audience who is used to seeing depictions of Passive Victims.

The ad also builds empathy by making heart disease feel directly relevant and recognisable to British audiences. The boy appears in an everyday, down-to-earth setting, similar to British food and drink family advertising (e.g. McCain’s 2019 ‘We are Family’ ad). Together with the boy’s speech style, the informal setting and the similarities to British FMCG/CPG advertising help to code Everyday Britishness, ultimately making heart disease an accessible and everyday topic, rather than a taboo.

By breaking the fourth wall and talking to us informally on our level (“just 3 quid a month”; “our research starts with your heart”), the ad also codes Peer-to-peer Engagement, reflecting how culture is shifting away from brands and institutions presenting themselves as authoritative, expert entities, towards friendly, engaging peers. This helps the viewer feel involved in BHF’s cause on a personal level, rather than being side-lined, as in GOSH.

Compared to GOSH, this ad feels much more relatable, warmer, and playful. Of those who saw the ad, 73% were likely to support in the future, whilst only 59% would be likely to support after seeing the GOSH ad. This shows how understanding and harnessing both cultural and category codes can help create a successfully disruptive comms and ensure development of a ‘great’ ad.

The CEP™ Test is thus an effective way to measure emotive power, comparing within (and across) categories in order to help us understand category norms. Using semiotics, we can not only decode how and why an ad scores a certain way on the CEP™ Test, but we can also uncover cultural and competitor norms in order to identify key ways to disrupt a category.

To find out more about our PrismCEP™ research approach, contact Maria Victoria O’Hana or Jemma Ralton