Our Thoughts

Owning Up Premiumisation in Supermarket Own Brands

Throughout COVID lockdowns, and post-Brexit stock shortages, supermarket own brands have continued to be familiar cultural pillars, a reassuring presence on the shelves and in the cupboards of UK consumers. But, while own label ranges have long been functional signifiers of stability and reliability, this category has subtly been undergoing a significant shift over the last few years.

Own label products are not often a site for much marketing reflection. A focus on design and culturally resonant messaging has often been seen as less relevant in a space typically defined by value. But even value has an aesthetic and lexicon.

Functionality was for a long time the key communication for own brand value ranges, aesthetically this meant plain white packaging to communicate a ‘stripped back’ and basic nature. The use of bold primary colours for text and highlights communicated approachability due to their association with child friendly products, and easy engagement brands like McDonalds or Google. From a language perspective range descriptors conventionally highlighted this functional and rational aspect, e.g. “Essentials”, “Basics”, “Savers”, or “Smartprice”. This sense of functional benefit was embedded even at the premium end of the own brand hierarchy, where there has long been a focus on communicating tangible benefits, e.g. “Taste the Difference”, or “The Best”.

Functionality was for a long time the key communication for own brand value ranges, aesthetically this meant plain white packaging to communicate a ‘stripped back’ and basic nature. The use of bold primary colours for text and highlights communicated approachability due to their association with child friendly products, and easy engagement brands like McDonalds or Google. From a language perspective range descriptors conventionally highlighted this functional and rational aspect, e.g. “Essentials”, “Basics”, “Savers”, or “Smartprice”. This sense of functional benefit was embedded even at the premium end of the own brand hierarchy, where there has long been a focus on communicating tangible benefits, e.g. “Taste the Difference”, or “The Best”.

For a long time, this functional aesthetic was successful, for example Sainsbury’s Basics range grew in sales by 40% per year after its initial introduction. But culturally our expectations of own brands have been changing, simplicity and rationality can no longer be the whole of the own brand story.

Firstly, a greater sense of complexity and sophistication is entering the own brand space, even among ‘value’ offerings. An example of this can be seen with Ocado’s new line of own brand products. The range moves away from the simple functionality of primary colours and rational language to embrace more complex ‘jewel tones’, and ‘foody’ language such as “petits pois” for their frozen peas, all the while continuing to market around affordability.

Alongside this shift towards a greater sense of sophistication, we can see the growing removal of the Masterbrand. Where it once was Sainsbury’s Basics, Morrisons’ Savers, and Asda Smartprice, own brands are increasingly being distanced from their ‘owners’. Aldi and Lidl have long pursued a policy of ‘anonymous’ own brand products, under a variety of other makers names, e.g. Aldi’s “Moser Roth” confectionary brand, “Ferrex” power tools, or “Power Force” cleaning products, and Lidl’s “Belbake” home baking range, “Freshona” frozen produce, or “Deluxe” deli foods. By attributing own brand products to stand alone makers, a greater sense of expertise in the products creation is communicated, heightening the perception of product quality.

An interesting alternative to this approach can be seen with Morrison’s “Market Street” concept, under which the Morrison’s Masterbrand can retain a presence, while their own brand products are grouped under the banner of various traditional artisan retailers (e.g. “the Fishmonger’s”, “The Grocer’s” or “The Baker’s”), dialling up the sense of products that are the result of dedicated craft, and framing the brand as a continuation of the heritage of the British high street. This image is further reflected in their communications, which have at times directly linked the store to a traditional market place.

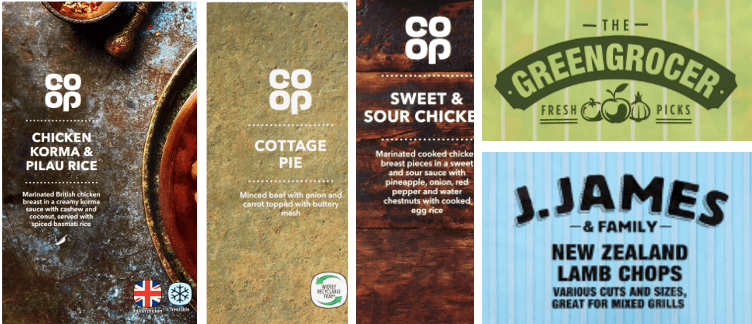

The influence of the global ‘craft’ movement, first witnessed in the coffee and beer categories before spreading to baking, spirits, and confectionary, is increasingly felt across culture. As this example shows, craft is even important in the own brand space, a development that has clearly been noted by Morrisons’ competitors. Sainsbury’s, for example, has quietly shelved their Basics range over the last few years in favour of own brand sub-ranges that reference a variety of assumed traditional makers and retailers, such as “J James & Family”, “Hubbard’s Foodstore” or the “Stamford St. Food Company”. This indicates the presence of a general move within own brands from a focus on rational functionality towards a greater sense of storytelling, heritage and craft.

Strategies like this do however have their limits. A similar move by Tesco to rebrand their fresh produce under the name of various “farms” was met with push back from the farming community and labelled as “fake farms” in the media, though these farm brands have remained within the Tesco range.

A subtler approach to communicating craft is achieved through growth of the signification of makership in the own brands space. Co-op’s range of ready meals, for example, employ imagery including rich natural textures such as rough wood and stone finishes, resembling traditional kitchen and workshop surfaces. Another approach involves the use of patterns and background detailing that connote traditional chefs, butchers, or grocers’ aprons.

Overall, we can see that it is increasingly necessary for supermarket own brands to not simply offer value, but to communicate compelling cultural narratives of craft and heritage. Semiotics can provide an illuminating lens on how a large-scale cultural movement such as craft, can manifest at a category level, and can help brands to identify the most culturally resonant messages within a given category.

3 key takeouts for brands:

- Narratives of simple functional value are no longer compelling on their own, and need to be fused with greater storytelling and cultural meaning to make them compelling.

- Communicating a sense of craft, heritage, and sophistication are increasingly culturally relevant ways of doing so with own brands.

- But in light of this, is it necessary to reframe the role of the Masterbrand? Would an own brand range work better if distanced from it?

If your brand is grappling with these or any similar cultural challenges, please get in touch. We’d love to help!

Mark Lemon, Associate Director