Our Thoughts

Beyond “Sustainability” Communicating brand ethos with clarity and cultural relevance

A positive environmental and social impact have become essential traits, or at least ambitions, for any brand over the last few years. And while consumers become more discerning about eco-friendly promises, we’re also seeing a kind of cultural exhaustion around the repetition of key words and claims. 60,000 tweets mentioned “Sustainability” on Earth Day (22nd April; Pulsar). Brands across categories have turned to the term “sustainability” to cover a vast range of purposes, claims and aspirations. Yet cultural associations between sustainability and its duplicitous twin – greenwashing – are rife. Digital culture enables consumers to know very quickly when a brand is using ‘sustainability’ claims to divert attention away from the reality of its environmental and ethical track record. Brands that have sustainable policies, it seems, may be best avoiding the ubiquitous term altogether and can gain distinction by adopting a more specific vocabulary.

This article looks at key ways brands are using semiotic and linguistic cues to communicate sustainability without saying: ‘we’re sustainable.’

“Regenerative” has been on the rise, particularly in fashion. A term that carries connotations of hope and renewal, “regeneration” appeals because it suggests a positive impact rather than just minimising harm, as Carol Shu of North Face has noted (Financial Times, 2 April 2021). Regeneration has a therapeutic context, associated with healing, restoration and resilience from a biological perspective. In urban development, ‘regeneration’ signals improvement and rebirth. Re- prefixes are prevalent across brands: Prada has created a line called “Re-Nylon”; Girlfriend Collective encourage use to “Recycle. Reuse. Re-Girlfriend.”; while many FMCGs move to packaging refills. The re- prefix suggests repetition, ultimately meaning ‘back’ and ‘again’. Even such terms as ‘renaissance’, ‘redemption’ and ‘reincarnation’ instil the re- prefix with a sense of new life and promise in the cultural imagination. Such notions of a second chance hold particularly powerful appeal for new generations met with an ecological crisis they didn’t create.

In a sustainability context, “regeneration” has its roots in agriculture, fibre-farming, and biologically self-renewing materials. When used as a substitute for ‘recycling’, the resonance of the term itself (and the brands who use it accurately – e.g. North Face) is diluted. In a way, the term “regenerated” can distract from product origins, and render actual sourcing processes opaque – suggesting that material recycling is the ultimate goal, regardless of impacts on farmers, indigenous populations protecting biodiversity, and labourers across supply chains. Countering this, merino wool pieces by Sheep Inc feature a scannable tag that reveals the item’s provenance and carbon footprint. When referring to “regeneration”, brands need be sure they do so with the traceability, and intersectionality, consumers will expect and demand.

Another term on the rise is “Net Zero” – one that seamlessly intersects with Netflix’s brand name, while representing their goals for 2022. Semiotically, “zero” signals the absence of harm and impact, while “net” connotes a cover-all, interconnected solution, as well as having a tech and digital slant signalling modernity. As such, “Net Zero” has a reassuring quality – an ecological ‘safety net’ through which nothing falls to environmental destruction.

However, we’re seeing brands start to go beyond net zero. Allplants are one example, focusing on ‘putting back in more than we take’. While “Net Zero” implies no further negative impact, ‘beyond net zero’ is a commitment to positive impact. Increasingly, brands frame their impact as a partnership or collaboration with nature, rather than purely an attempt to mitigate natural resources.

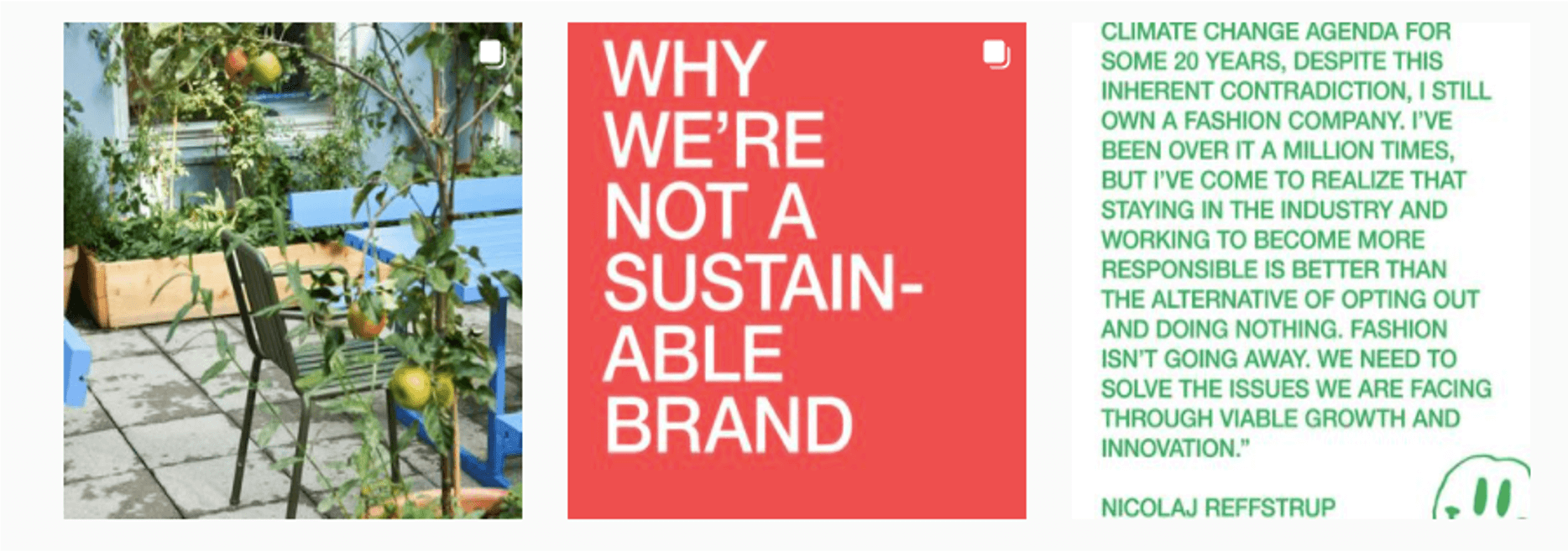

Another approach is outright admitting to not being sustainable at all. Instead of resorting to greenwashing or overstated claims, brands including Ace & Tate, Ganni and Noah are pointing out that production always comes with emissions, excess, and environmental damage. Rather than being defeatist, these brands acknowledge that sustainability is a “process” (Ace & Tate) and that small progress and active awareness are important steps (Noah). This seemingly counter-intuitive approach has a leading example in Patagonia’s “don’t buy this jacket” campaign (back in 2011).

Since at least 2018, Noah have championed other companies who lead the way in sustainability. Today, the impact of coronavirus has seen many brands celebrate and collaborate with other companies, or indeed their competition (e.g. Tesco encouraging people not to buy beer in-store, given the re-opening of pubs). This approach has a natural place in relation to sustainability issues. Highlighting your brand’s shortcomings and contradictions – alongside clear, action-based outlines of your commitments – communicates dependable openness, as well as laying out a benchmark against which to assess progress.

Given that social media has propelled awareness of ecological and ethical issues, it’s fitting that culturally meaningful social content is a vital way to communicate brand efforts and purpose. While fast-paced trends change the digital landscape constantly, purposeful impact and progress are constant, even if their representation evolves. Understanding “sustainability” terminology, and the changing cultural connotations of different approaches – of which only a small handful have been highlighted here – is key to building lasting connections and consumer trust over time.

Key takeouts for brands:

- Consider language beyond the ubiquitous term “sustainability” to communicate your environmental impact and aspirations.

- Can you go beyond just mitigating impact to making and communicating your positive impact on the environment?

- Avoid overclaims and greenwashing by being refreshingly open and honest about your progress towards your environmental goals.

Katrina Russell, Project Director