Our Thoughts

The Midwife of Invention Deliver successful innovation with Cultural Insight

If necessity is the mother of invention, then cultural insight is its midwife. A report by Nielsen estimated that 85% of FMCG/CPG innovation fails, i.e. products are not around after 2 years. So innovation/NPD is hugely risky. But, near misses can be transformed into sustained success if product innovation is delivered with cultural relevance.

Cultural relevance is an essential way of explaining why we do and don’t do things. Yet, most major brands use it in an ad hoc and occasional way, if at all. Just as needstate/gap analysis, segmentation, U&As, etc. are a core foundation of any brand or especially innovation strategy – and more importantly investment/prioritisation strategy – so cultural understanding should be a key, base camp input to explain and create clear analysis of how your category and brand can actionably respond to consumer worldviews. Right now, they will almost certainly be changing, either rapidly or subtly, so there is a huge opportunity to ensure your decision making has cultural insight as a clear input with an actionable map of how culture might be impacting your brand and business when evolving new products, communications, and positioning.

Indeed, according to a report conducted by McKinsey, for the past 10 years consumer packaged goods (CPG/FMCG) have struggled to deliver growth because businesses generally took small incremental steps with existing brands (apart from emerging markets). The steady but relatively slow growth of global CPG/FMCG businesses indicates that the traditional business model isn’t working in the West.

As is well known, the traditional CPG/FMCG model was based on manufacturing and distribution at scale, supported by expensive media and promotions, with regular news/innovation to keep it fresh, and with products sold through a small group of large, expected retailers. This model created strong barriers to entry for any newcomers and so the market tended to be dominated by the big established players.

But this model is adapting to new players who, at small scale, are able to capture a lot of the growth. They have overcome barriers to get on shelves, because they can more specifically meet the needs of targeted consumer segments in a way that mass brands no longer do. Big brands have responded successfully in the pandemic return to the ‘big shop’ which has seen consumers seek reassurance in trusted brands. But it is likely that this is a temporary interlude and that we will continue with the trajectory of the small & local is beautiful approach.

Why is that? The two reasons have been well-rehearsed: first there is a new demographic driving this change – Millennials/Gen-Z, and second there are more competitors grabbing the share of consumer spend. Even if individually they don’t challenge the classic brands/businesses in terms of market share, as a collective group these new smaller brands represent an increasingly big chunk of the market. Of course, this isn’t only represented by CPG/FMCG, it also applies to apps, tech, & media.

The key then to overcome the slow growth of an increasingly outmoded model – and to take advantage of the new model in an increasingly confident marketplace emerging from the pandemic – is innovation.

While social culture and working patterns are still in flux as we emerge from the pandemic, that uncertainty also creates exciting conditions for innovation, as the new culture being established also energises new consumer needs, unmet opportunities, and emerging product and category gaps.

For instance, this summer due to Covid, British restaurants sprawled their tables into the roads, and traffic ceased in certain areas. This is, of course, the way that innovation happens. People discover a new way of doing things, and those new ways spread (or wither and disappear), and then they become locked into behaviour and part of culture as a whole. BUT the underpinning of cultural relevance was crucial to the success and endurance of the innovation. Consumers appreciated the functional answer to Covid health & safety, but packed out the restaurants excitedly because of the cultural dynamic of having a sophisticated, al fresco European holiday experience at the very moment they were denied the opportunity to go abroad for that vacation. This was risk that worked. The strong cultural value narrowed the margin of innovation error.

So, how can you get culture right for innovation? As is well known, there are only two types of innovation: Small and Big.

Small innovation – also called churn innovation – is concerned with incremental changes, additions to existing formats, e.g. new flavours, increased convenience (plastic squeezy packs for ketchup vs traditional glass bottles). Small innovation adapts existing products to meet unmet needs.

Big innovation, by contrast is concerned with ‘blue ocean’ disruptive changes that can enhance lives, create new categories, and transform behaviours, e.g. the mobile phone. Big innovation introduces fundamentally new solutions and new products to meet unmet AND even unknown needs. They can even ‘create’ new needs, e.g. the creation of the hair conditioner segment.

Both are valuable ways of innovating. While Small innovation is more cost effective, less risky, and is a response to often stated unmet needs or a way to refresh a brand, it is the Big innovations that can make a company’s fortunes (it can also of course break them).

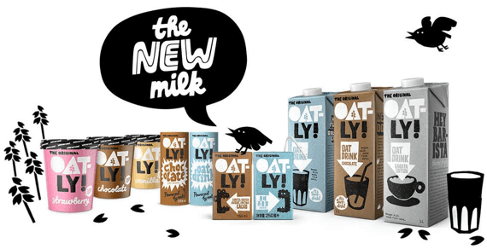

Take as an example the rise of the plant-based milk category. Rice & almond milks had been around for many years in specialist health stores targeting lactose intolerant consumers, and positioning themselves as functional health alternatives (and using clinical white and blue to signal that value). But culture shifted; new debates around environmental sustainability put the dairy industry in the spotlight, wellbeing concerns promoted plant-based diets, broader bottom-up social shifts elevated craft-style processes, tones of voice, and street-level brand visuals (e.g. craft beer), all creating the perfect cultural space for a brand like Oatly to enter the market and exploit the lifestyle gap. Having identified the Big innovation opportunity, they have subsequently rolled out a series of Small innovations across the brand, including Barista, custard and yoghurt variants.

Cultural insight would have tracked the fundamental cultural change around dairy and non-dairy, and would have identified the new narratives visual and language cues needed to introduce a non-dairy brand at the very moment that gap was emerging, and before consumers started to change their behaviour. As I argued in a previous article, culture comes before behaviour, and while you can’t predict the speed of change, cultural insight can reveal convincingly that it is coming in the next 2-5 years, and what it will look like. Tracking culture in this way provides more chance of being at the front end of any innovation gaps & opportunities.

Traditionally, innovation of this kind requires research at the front end – i.e. to identify potential areas of opportunity based on unmet consumer needs – typically classic U&A, usage and attitude – investigating existing products in the market. But what often emerges from the research is functional, rational insight which identifies gaps in the market. Or sometimes the research is conducted from a tech angle, i.e. we have some technology we’ve just created, what gaps can we fit it into? But even the questions you ask in the U&A can be influenced by findings from cultural insight and therefore be directed more powerfully.

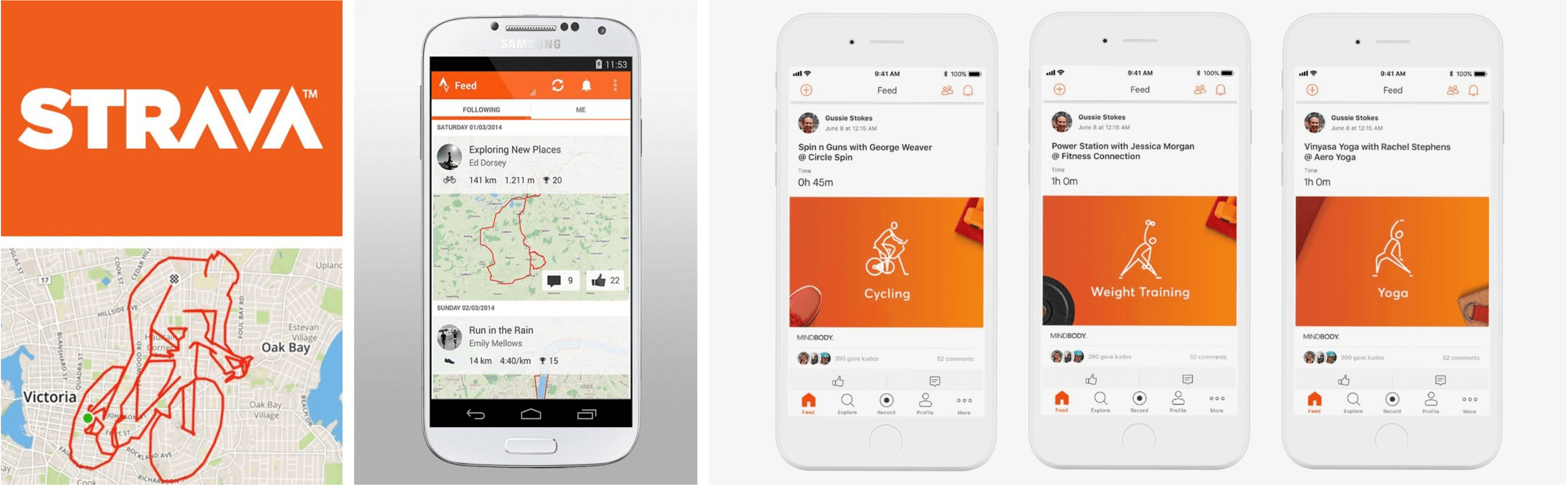

Traditionally a ‘gap’ has been defined as a segment of the market that isn’t being met. Take Strava, the social exercise tracking app, as an example of that kind of ‘gap-filling’ innovation. Before it was created exercise apps already existed, for recording personal progress. Similarly, social network apps were already well-established before Strava emerged. The Big innovation that Strava represents though is the fusion of the two forms: Fitbit meet Facebook. Creating friendly competition and peer group support and pressure satisfies strong cultural desire for connection/belonging and friendship, fun, AND the need for wellbeing through exercise. In this way, brands need to understand more about how they fit into people’s lives rather than purely as a retail product offer online or offline. They leveraged tech to get to the front edge of a fitness & community cultural and behaviour change. Only by tracking culture change can that be achieved.

While classic U&A research would have revealed the gap for fusing the two experiences, cultural insight can assist with understanding the emergent narratives & visual/language cues of connection, community, friendship, fitness, exercise, wellbeing – and can offer direction on how to fuse them all seamlessly. This is fundamental for developing the identity & TOV of the brand, the look, feel & interaction of the app (UX & UI), even the services which can be offered to consumers, all of which are crucial for transforming a rational, functional product innovation into a meaningful brand experience.

In research people can state their needs, but Cultural Insight can tell you where that need comes from. By having this understanding of the cultural why behind the need state, you can identify the actionable elements you need to maximise the cultural fit of the product innovation and effectively capitalise on the gap. Pushing the cultural buttons is key, and it’s hard to ‘research’ emerging codes as people don’t really know they are assimilating them. Breakthrough innovation without culture is a tough ask.

So if you are doing ‘gap analysis’ for innovation, cultural insight can be a powerful aid to define gaps. BUT, crucially, the really powerful role for cultural insight in innovation and NPD is in identifying a cultural need that is not being met well enough. Cultural fit can maximise commercial opportunity. Emerging codes, if regularly tracked, can become part of your predictive armoury, helping isolate the cultural insight that WILL drive tomorrow’s innovation, comms and consumer response.

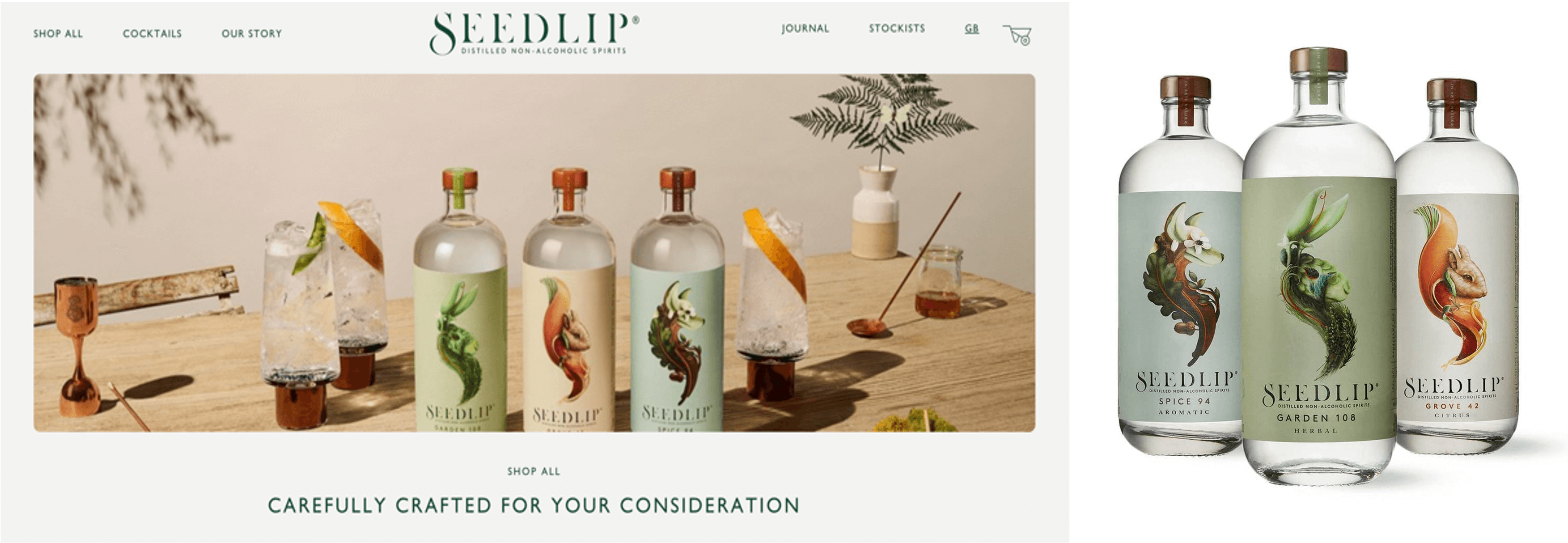

Take non-alcoholic spirits. Before they were created, soft drinks were meeting the need to avoid alcohol in a public group setting in a bar or pub. BUT they were failing to meet an essential cultural aspiration to fit in with the group, and participate in an adult socially sophisticated moment, and not signal your ‘childish’ essence by consuming a soft drink. So research no doubt identified a gap for non-alcoholic spirits, which NPD could create to meet the unmet consumer need to mirror standing in a bar with a drink that looks like a gin & tonic, giving you permission to be with the alcohol-drinking group. But while that insight generated the innovation opportunity, cultural insight applied to an analysis of the spirits drinking moment and category codes could identify the narratives & visual/language cues to be employed to ensure the development of a meaningful and relevant brand proposition, e.g. serving with a mixer and a slice of lemon, the role of botanicals, representation of flavours, product descriptors, provenance & craft makership processes, bottle formats, the right fonts, liveries, illustrations, etc.

Seedlip’s successful Big innovation in this category folded together the product innovation of non-alcoholic spirits together with the cultural power of spirits category cues, to create a successful brand that not only delivered on unmet needs, but did so in a way which was authentic to the emergent craft codes of the category. This small start-up created a new category and soon after attracted the attention of a global drinks business, Diageo, who invested and scaled-up the brand. The identification of a market gap and the successful development of a drinkable product was only half the story for the brand which owes so much to its culturally relevant design, TOV, & values.

So, following Seedlip’s example, imagine you’re a brand steward and you’ve done your consumer research and you’ve come up with a piece of innovation that’s about speed or convenience, or efficacy, or you’ve decided that there’s a gap in the market because nobody has a product that does ‘this great thing’ (e.g. hair conditioners as a supplement to the shampooing moment). Where cultural insight is really valuable then for innovation, is where you have your early stage opportunity concept on the table – in advance of execution – and need input and inspiration to ensure your execution is culturally relevant and not contradictory. Using semiotics and language analysis, cultural insight can identify which codes to maximise and which to minimise to ensure that the new innovation aligns both with culture and brand contexts, and in this way stands out from other competitors also innovating in the same market gap.

A view of the male grooming category also provides a useful illustration. Gillette has always been about innovating around tech to achieve a closer shave. Dollar Shave Club broke the category mould by signifying functionality, value and convenience through its direct to consumer proposition.

But Harry’s incremental change to the category – its Small innovation – added the cultural power of men’s grooming tradition and heritage, elevating it beyond tech functionality and convenience. The direct to consumer delivery gave that brand an advantage over Gillette but its success wasn’t purely anchored in convenience which was only part of the innovative nature of the brand. The real innovation was in pairing a 21st century subscription business model with a 20th century male grooming narrative.

Essentially, Harry’s brought the traditional barber’s experience into your home, while DSC merely signalled that they could provide a classic home shaving experience conveniently. Harry’s added a strong cultural value to a domestic shaving category that had lost connection to the excitement, theatre, and pleasure of visiting a barbers and was purely signalling its benefit as convenience and basic efficacy.

While Gillette became more functionally efficient at mastering your face, Harry’s spotted a gap for a brand which met the need for pampering and pleasure in the grooming moment. In doing so Harry’s innovative AND culturally relevant proposition is actually the ‘best a man can get’ because it is closest to a shave in a barber’s chair, the height of grooming sophistication and pleasure. By reminding us of the beauty and theatre of an old-fashioned barbers, Harry’s has stolen Gillette’s clothing. Harry’s innovation was identifying a gap in the home for the theatre of the barbers shop and the expert authenticity that underpins it.

Cultural insight can also assist in identifying activation opportunities to support the relevance of the product innovation. For instance, a natural next step for Harry’s would be to create some actual barbers shops (a la Ted Baker), as both a marketing exercise and brand theatre to sustain the narrative of how Harry’s brings the culture of the barber into your home, and evokes the heritage in a contemporary and excitingly relevant way, transforming your grooming ritual.

If brand guardians aren’t using cultural insight for NPD they are missing an opportunity; the difference between success and failure can be very small. In most categories innovation is hard, there are often no real gaps, consumers are already well served, and own label is catching up in terms of quality and acceptance… so the small details matter. What cultural insight adds to the innovation process, is explaining the context the product sits in so it can have a strong cultural fit, which can make the extra difference to ensure stickier innovation. It helps identify what businesses should or shouldn’t do in bringing a product to market in a way which instantly makes it culturally relevant. By marrying product innovation to cultural relevance you can increase the likelihood of commercial success, and like a midwife, bring your new product into world with greater confidence.

3 key takeouts for brands:

- Cultural Insight as an Actionable Strategic Innovation Map: Use cultural insight as a clear input to create an actionable map of how culture might be impacting your brand and business when evolving new products, communications and positioning.

- Track Cultural Change to Spot Market Gaps: Cultural insight can be applied to track fundamental cultural change and identify the new narratives, visual and language cues needed to introduce a new product at the very moment that the market gap is emerging, and before consumers start to change their behaviour.

- Consider using cultural insight where you have your early stage opportunity concept on the table: In advance of execution, cultural insight can be used for input and inspiration to ensure your execution is culturally relevant and not contradictory. It can identify which codes to maximise and which to minimise to ensure that the new innovation aligns both with culture and brand contexts, and stands out from other competitors also innovating in the same market gap.

Alex Gordon, CEO