Our Thoughts

The Big Sleep How sleep culture is changing

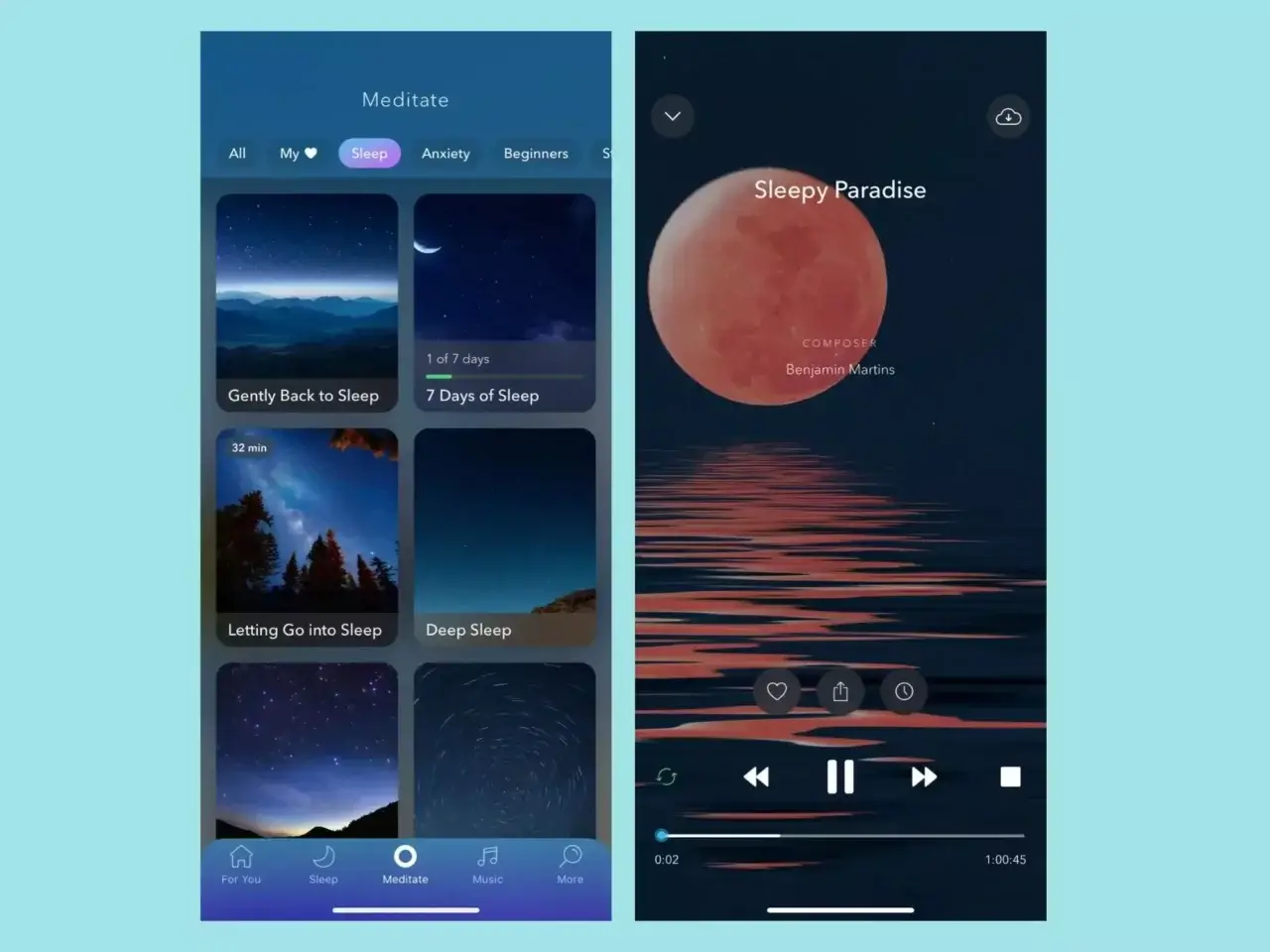

Sleep is imbued with cultural meaning. Conventional wellness culture has paid a great deal of attention to the ‘active’ aspects of wellness & wellbeing – how we eat, drink, exercise, and so on. Sleep health, however, is increasingly integrated into our waking lives. In recent years, a plethora of apps, supplements, and approaches are all geared towards framing optimised sleep as, variously: a consumable lifestyle choice, a personal feat, and a way to resist a culture of unrelenting productivity.

Sleep as a cultural idea

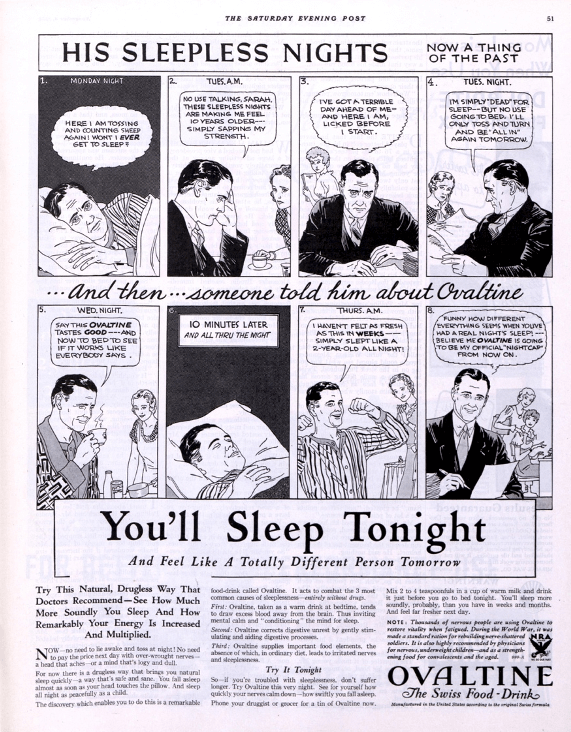

A quick look at the history of mattress, bedding and Ovaltine advertising – i.e. the advertising of sleep – makes the connection between sleep and culture immediately apparent. Several 1950s ads positioned sleep as the route to masculine productivity and ‘strength’. In one Ovaltine ad, we see a suited man struggling with sleep, before telling his concerned wife (presumably) there’s “no use talking”, and exhausted in the office. After Ovaltine restores his sleep, the man is shown flexing his muscles in the morning, and surrounded by women at work admiring his efficiency.

1980s US mattress ads reflect a broader socio-political emphasis on technological efficacy leading to success, along with a focus on the importance of physique and personal beauty (see ads for the Beautyrest mattress).

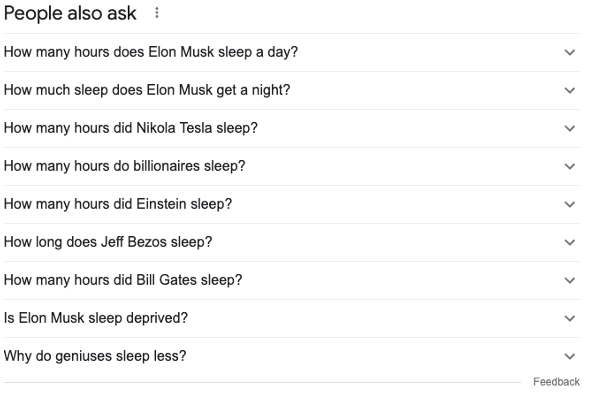

In culture at large, the amount of sleep required by political leaders and entrepreneurs has long been a source of fascination. The idea that a certain kind of “successful” person sleeps fewer hours has been a residual pop cultural phenomenon. Bond villain Gustav Graves notoriously never sleeps [“Mr. Bond – I have to live my dreams”] while Martha Stewart reportedly sleeps 4 hours a night.

In the later 20th century, there seems to have been a shift, then, from lack of sleep as a weakness to sleep itself as a kind of weakness – an apparent antidote to productivity. Conversely, energy drink advertising has dominantly aligned ‘alertness’ with the ability to do more and produce more.

Sleep as success

With Covid-19, attitudes to sleep (and wellbeing in general) have shifted. Sleep schedules were disrupted in varying ways: by the stress of the pandemic, the symptoms of coronavirus itself; the rise of working from home or shifted work hours for many.

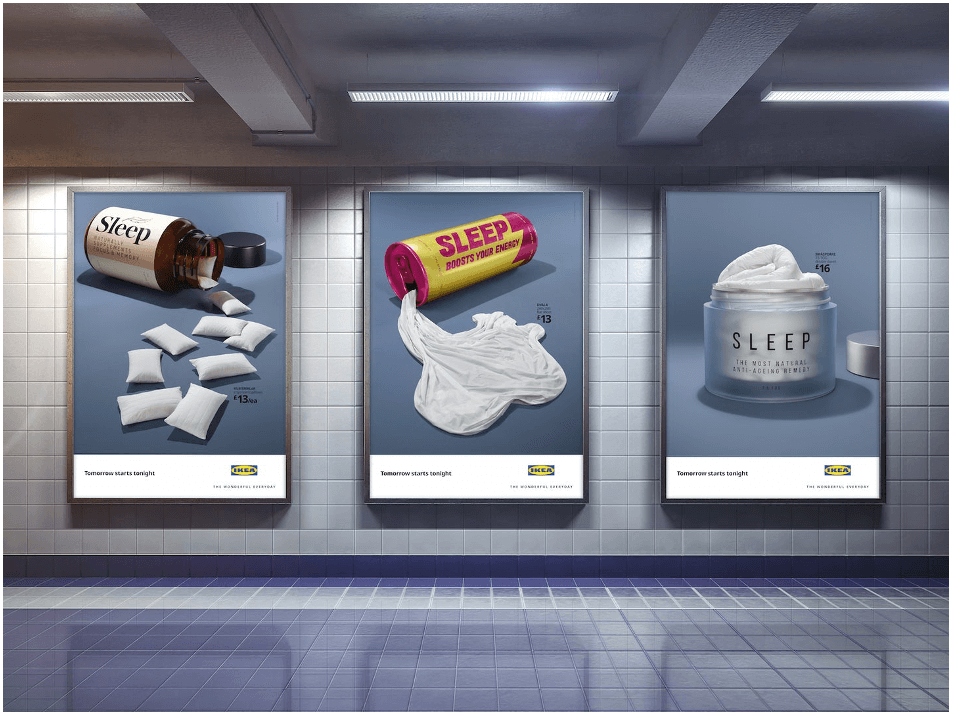

These factors saw sleep more overtly situated in the context of mental health, and the need to make time for oneself. Accordingly, Ikea’s 2020 ad campaign created a series of metaphors likening comfortable bedding to sleep supplements and anti-aging creams.

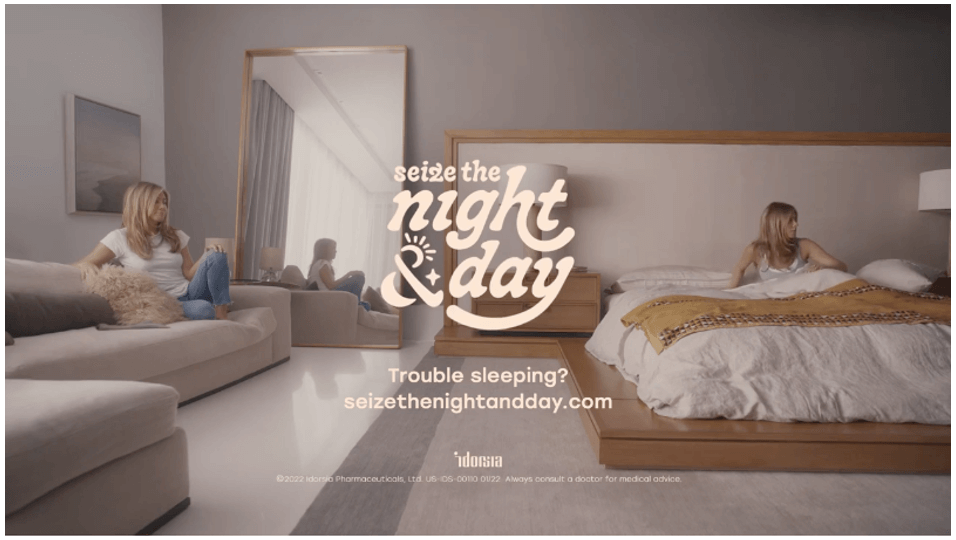

More recently, brands have addressed topics previously less represented in mainstream sleep conversation. Jennifer Aniston has partnered with Idorsia in a witty campaign highlighting her insomnia. The sleep supplements ad marks a departure from celebrity ambassadors typically celebrating their strengths, to now candidly addressing their limitations and frustrations.

The ad’s self-referential humour adds levity to the subject of insomnia, which has more typically been shrouded in anxiety and conceptual & physical darkness. Overcoming insomnia is here framed as “seizing the night and day”, rather than focusing on the burden of sleeplessness one is trying to move away from.

The meditation and sleep app Calm has partnered with LeBron James, who advises “you need to lay down in bed to focus your head” in a recent campaign. As part of a wider shift away from framing physical restriction as a source of achievement, sleep has been positioned as a source of strength and accomplishment.

Sleep & rest as resistance

Tricia Hersey – artist, theologian, activist and writer – started The Nap Ministry in 2017, creating a framework for rest as a form of deep healing. Hersey recognised that Black Americans are facing the largest amount of sleep deprivation in the US. She traces this to slavery, in which Black bodies were treated as machines for the goal of profit. Sleep and rest, as spiritual freedoms, are integral to Black liberation. They are acts of resistance to “grind culture” and to forms of capitalism rooted in white supremacy. The Nap Ministry’s framing of rest as resistance has roots in Black scholarship – it is part of a decolonising movement, not a commoditized wellness movement. Hersey’s book, Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto, is out this year.

3 key takeouts for brands

- Insomnia and adjacent sleep issues have conventionally been framed as highly isolating, anxiety-ridden experiences. Emergently, brands can address sleep issues with a focus on light-hearted warmth and approachability.

- Sleep culture is connected to shifts in work culture, and evolving notions of ‘productivity’ and ‘success.’ See, for instance, the exposure of ‘girl boss’ as an exclusionary form of feminism. Paying attention to how these ideas of identity in relation to productivity & rest are changing and culturally (de)constructed is vital to any category.

- Understand the cultural storytelling behind prevailing perceptions around sleep, and examine how unilaterally those stories are shared across communities. Which stories haven’t been told? Can your brand platform help these stories be told & shared – in a credible and relevant way?

Katrina Russell, Associate Director