Our Thoughts

Same Faces / Different Places Foreign Brand Ambassadors

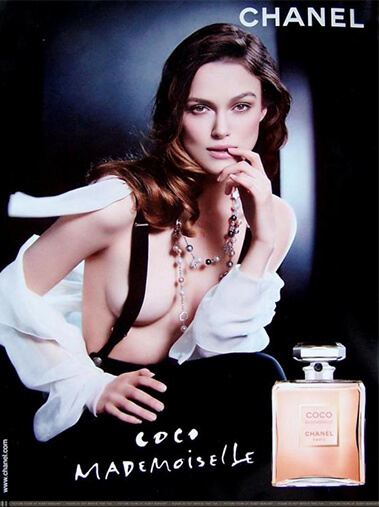

Walk into a luxury mall in East Asia, and you could be forgiven for momentarily forgetting where in the world you are. From Keira Knightley wearing Chanel (in Japan) to David Beckham driving Jaguar cars (in China), it has long been commonplace to see foreign glitterati fronting large, multinational brands.

Traditionally, brands have tended to opt for Anglo-American ambassadors to reinforce their products’ origins in the ‘Western’ world— thereby evoking dated, yet deeply-ingrained, notions of superiority in consumers’ minds. For a Chinese shopper, Beckham’s presence might carry lingering connotations of prestige from the 1970s— when under the Open Door Policy, a person’s ability to secure Western imports marked exceptional wealth and status. For a shopper in Indonesia or Vietnam, it might evoke colonial hierarchies that— until recent decades— decreed cultural products from Europe more sophisticated than local ones, and therefore more ‘premium’.

By contrast, foreign ambassadors from within the realm of East Asian pop culture engage consumers via a different logic of desire. Consider how companies across East Asia harness the iconicity of South Korean ‘Hallyu” stars: from Jun Ji-Hyun fronting Gucci posters (in Singapore) to Kim Woo Bin decked out in Calvin Klein (in Shanghai), the trend has gained so much momentum that some national governments, like China’s, have even introduced protectionist quotas on these models. If their Western counterparts connote distant prestige, then by contrast, Hallyu models signal East Asian ‘Sasaeng’ cultures with their distinct mix of up-close-and-personal, yet reverentially removed, fanaticism. Their appeal is in the paradoxical way that they embody both accessibility and mythicality— an aura that, by association, transfers onto whatever watch or t-shirt they happen to be photographed in.

Ultimately, though, it might be worth asking how far these attitudes towards foreign brand ambassadors will hold up in the near future, as East Asian standards of living rise and global balances of power shift. If recent ad campaigns are anything to go by, it would seem that consumers have gradually become less willing to accept foreign cultures as assumed, yet opaque, authorities on quality. Instead, they seem to be gravitating towards brands that contextualise quality in ways that are close to their own experience— and thus intellectually, if not emotionally, relatable.

Consider SK-II’s ‘Marriage Market Takeover’, which went viral in China by featuring born-and-bred Chinese women confessing to the social pressure they faced to get married. By using local women and families as the face of the brand, SK-II was able uncover— and then mobilise against— cultural anxieties that would otherwise have been inaccessible to them as a large MNC. Another successful strategy is represented by Lululemon’s local ambassador programme, which exists in several East Asian countries including Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea. Like SK-II, the brand utilises local representatives to forge an image of relatable human warmth, and demonstrate emotional proximity to consumers’ lives.

Do foreign faces still sell, or must brands find other ways to reach consumers across the fault lines of cultural difference? I would suggest that as East Asian shoppers grow more empowered and knowledgeable, they will increasingly search for cultural narratives that are tailored towards, and transparent to, them. Perhaps in five or ten years’ time, a picture of Keira Knightley or Jun Ji-Hyun might not evoke the same awe that it used to.