Our Thoughts

From models to body bottles

This summer, Dove U.K. launched a limited line of seven body-shaped bottles that ranged from the hour-glass shaped, to the ‘boy-shaped’. Supposedly proving that “beauty comes in all shapes and sizes”, these bottles have been mercilessly ridiculed by vocal feminists and bemused observers alike. Why the cold shower?

Some might say that the body bottles do too little to push the envelope on representation. Despite their varied shapes, the bottles still connote several deeply ingrained, conventional standards of beauty— consider their ivory hue and smooth, symmetric, feminine shapes. As a range, moreover, they smack of crude simplification: can Dove claim to represent the whole gamut of physical diversity through only seven types?

But perhaps these arguments miss a more important point. It would be impossible for Dove— or any brand— to champion diversity by literally reproducing every body-type that exists, thereby affording it “representation”. The issue, then, isn’t that Dove’s strategy doesn’t go far enough; it’s that this strategy is fundamentally out of step, incongruent with emergent cultural beliefs around body positivity.

To begin with, Dove’s focus on bottle shapes signals “Real Beauty” as a superficial, not substantial, quality. Despite their diverse forms, each bottle contains the same cream formula that has been used for years— beauty here stems from shallow visual transformations. No surprises that this message sits badly with consumers who, increasingly, associate beauty with inner grace and dynamism, rather than superficial style: think of how brands like MAC and Pat McGrath have thrived by representing beauty as the confidence to express one’s innermost, kooky self.

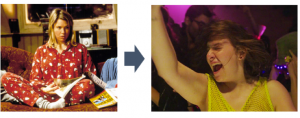

By encouraging consumers to pick bottles that match their figures, moreover, Dove compels them to actively consider— even fixate on— their physical appearances. Effectively, the bottles function like daily, in-shower reminders of consumers’ body-types— harkening back to the insecurity and body-obsession that traditionally haunt women under patriarchal pressure (think of Renée Zellweger as Bridget Jones, neurotically logging her weight on Christmas day as “140 pounds plus 42 mince pies”). Dove, then, falls short of the progressive self-love championed by emergent cultural icons— where women like Lena Dunham simply get on with having full, exciting lives in spite of their bodies, rather than obsessing over their figures and letting their bodies define them.

Body positivity is a fraught territory, which brands can navigate more easily with the help of cultural insight. By understanding how definitions of self-love are changing, brands like Dove can find new ways to liberate women from their beauty dilemmas, empowering them in truly meaningful ways.