Our Thoughts

Crowning Glory? Brands and the semiotics of crowns

Elvis may have been the ‘King’, and boxer Tyson Fury may have crowned himself with the moniker ‘The Gypsy King’, but given the excitement being generated around the forthcoming coronation of a real King – Charles III in the UK – and the role of crowns at the centre of that ceremony, there are some interesting implications for brands which employ crowns as key brand icons or logos.

Crowns have been used by brands to communicate their luxury quality and to convince consumers that ‘this brand is good enough for a king/queen’. It emerged from a European tradition in which royalty and aristocracy had the time and the money to indulge in leisure pursuits and consumerism long before the term was invented. So monarchs like Louis XIV of France and George IV of Great Britain both indulged in expensive decorative objects d’art and extravagant architectural projects (Versailles, Brighton Pavillion) to satisfy a desire to accumulate material objects. In doing so, they elevated the skill of the craftsman artisans responsible for designing those buildings and making those fine pieces.

Crowns have been employed in logos, or in the name – or both – to reflect and evoke the same kind of royal association, even though any connection may not be publicly known or even exist at all. So embedded has this visual trope become, that we as consumers have detached them from their original regal context.

Ritz Carlton, the luxury hotel chained owned by and part of the Marriott Hotel Group, and Rolex, the world famous watch brand, have both employed a crown icon for the same purpose – to communicate that their product is ‘fit for a monarch’, and superior to other luxury competitors who don’t have the benefit of utilising the strong cultural meaning of a crown icon.

Used in this way, a crown icon has become a well-established visual metonym – a short-cut – to create associations with or communicate the idea of royalty. When a brand which has no actual relationship to royalty (i.e. like Rolex & Ritz Carlton for instance) employs the crown icon, the consumer instinctively and irresistibly associates the brand with the supposed values of royalty – authority, luxury, quality, superiority, leadership (and by extension our deference). This elevates the brand beyond the basics of the everyday or even beyond the mere indulgence of ‘luxury’, but instead invests it with those same ‘mystical’ values of royalty. Rolex, Ritz Carlton – two different brands operating in two different categories, but utilising the same icon to signal their superior and special quality, and trying to convince us of their difference and distinctiveness versus their crown-less competitors.

In particular, for both of these brands, the crown icon is an attempt to link the brands to a European heritage connoting craft, heritage, expertise, which is revered particularly by consumers outside of that geographic region as a sign of excellence, reliability, and authentic ultra-luxury.

This association with a prestigious European heritage and quality is similarly evoked by the whisky brand Crown Royal, a Diageo brand mostly sold in the south of the United States, particularly in Texas where it has strong market share. The supposed European regal heritage of the brand is emphasised as crucial to communicating the brand’s high quality and believable luxury. The crown is represented in touchpoints (including pack) sitting on a purple cushion, just as it was on Queen Elizabeth’s coffin at her recent funeral and when carried for the state opening of the Scottish parliament (the red velvet crown is the crown of Scottish monarchs). The secondary packaging reinforces this coding of regal splendour by wrapping the bottle in a purple ‘protection’ bag and then in a purple presentation box. These layers of ‘luxury’ are loaded thickly onto the brand to connote a deep connection to an invented European heritage. This creates strong associations in the consumer’s mind with values of craft, prestige, luxury and high quality which enables Crown Royal to distinguish itself from other high-end whiskies and bourbons which anchor their luxury quality in North American craft distilling traditions (e.g. Gentleman Jack, Kirkland Canadian whisky).

BUT these connotations of royal quality have also been overlaid onto and adopted by everyday value brands, not only those associated with a more classic luxury positioning.

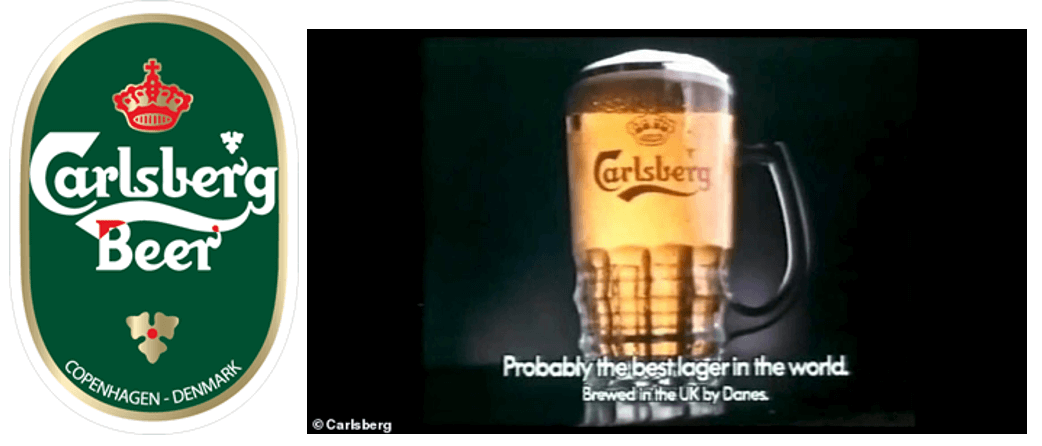

Carlsberg, for instance, used to provide their beer product to the Danish royal family which is why they adopted the icon for their brand. We as consumers don’t view that brand as a distiller to royalty any longer, (Carlsberg don’t reference their royal connection in advertising), we merely see the crown on their packaging and advertising and ‘read’ it as a signifier of luxury quality.

BUT the presence of the crown icon gave them permission in their 1970s and 1980s UK advertising campaigns to claim that they were “probably the best beer in the world”. We believed the claim, because it was backed up by the presence of the crown which gave credence to an otherwise unlikely and bombastic assertion.

Both Burger King and Budweiser – the ‘king of beers’ – have staked their claim to superiority, leadership, quality, and prestige by adopting the crown alongside other classic visual cues of faux European heritage. In the case of Budweiser, the crown sits prominently alongside other distinctive pack assets including heraldic crests, ribbons, and ‘official’ cursive script text declaiming the traditional brewing process. Burger King eschews all of those European craft signifiers, but has historically employed the image of a traditional ‘king’ avatar in their advertising – a bearded middle age man, wearing an ermine cape with a medieval ‘ruff’ collar.

The challenge for luxury brands is the ubiquity of crowns across the full spectrum of categories from value, to mainstream, to premium, to luxury. If both Rolex and Burger King employ a crown as their key brand icon then how are we to assess ‘true’ luxury? Which brand is authentically regal quality? Which one is really ‘fit for a king’? Perhaps both are in different ways, but an icon which was once a clear and certain signifier of special and unique quality is clearly undermined when it is employed by the producer of burgers on a mass scale and available to everyone. The point about royalty is that they were/are inaccessible, socially detached and elevated, and represented a refined and luxurious lifestyle unachievable to the mass. That might be the case still for Rolex, but Burger King certainly represents opposite, more democratic values, and that’s the key to its success. When a crown is used by both a luxury AND a value brand, the crown icon itself becomes devalued like the brands themselves.

Indeed, alongside this ‘cheapening’ of a key ‘royal’ signifier, the values once clearly associated with royalty by common public consent have been subjected to scrutiny over the last 25 years. Aggressive exposés by the tabloid media, and gossip across social media, have revealed the flawed ordinariness of the individuals at the heart of many royal families. From the indiscretions of King Juan Carlos in Spain to the rift between Prince Harry and his family, monarchy seems to resemble the narrative of a soap opera, rather than project an air of majesty.

Royalty, along with other institutions in which the populace previously invested their deferential respect – police, politicians, banks, mainstream media – has been revealed as flawed at best and exploitative at worst. There has been a slowly emerging paradigm cultural shift from reverence to rejection. This reversal from a culture in which authority institutions were placed above the populace in a top-down hierarchical structure, is increasingly being rejected by younger demographics who favour a new expression of authority which is bottom-up and reflects a more democratic, meritocratic, diverse, and inclusive value system. Under those conditions, revered brands are those which promote the makers and craftsmen at their heart, rather than the owners of the business. Brands which represent a bottom-up culture are those which promote clear ‘purpose’-based agendas around sustainability & sourcing, fairer treatment of employees, and redistribution of profits to charitable causes.

Crowns though, are very clearly associated with the increasingly outdated top-down culture. However patriotic we might be, the numbers of those who are less attracted to the concept of monarchy is rising in line with this increased rejection of traditional hierarchies of power. In a survey by British market researchers YouGov of more than 3,000 adults conducted this April, 35% said they “do not care very much” about the coronation, and 29% said they “do not care at all”. Coronation apathy is particularly high among younger age groups, with 75% of people aged between 18 and 24 saying they do not care “very much” or “at all” about the event, and 69% of those aged between 25 and 49 saying the same.

Against this cultural backdrop, brands like Rolex and Ritz Carlton can’t escape the fact that they represent a value system which is less aspirational than it once was. While their Boomer and GenX loyalists may remain unaffected in their commitment, the medium to long-term prospects for these brands are under question. Similarly, although brands like Budweiser and Burger King are more accessible mainstream brands, their use of crown icons tie them to outdated cultural values relative to more contemporary competitors in each of their categories, e.g. craft beers like BrewDog, Sierra Nevada or Ithaca Flower Power IPA, or burgers restaurants like Shake Shack and Five Guys.

But for many brands like these, the crown icon has become such a synonymous part of their identity that to remove it altogether would damage brand equity and undermine the ability of the brand to connect with its consumers in the same way. Rolex is such an established luxury brand that evolving its brand to reflect contemporary ‘quiet/understated luxury’ trends by erasing the crown in its logo (among other tactics), would lose its difference and distinctiveness vs its competitors, e.g. Omega.

So what can brands at either end of the consumer spectrum – from value to luxury – do if their brand is so connected to a royal essence through the use of a ‘crown’ icon? How can they ensure cultural relevance while maintaining their traditional distinctiveness and equity?

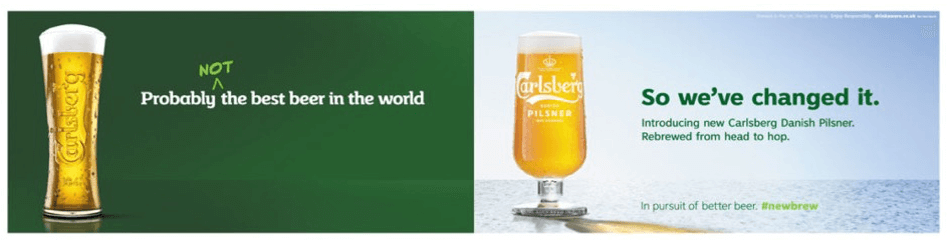

One answer is to take a leaf out of the Carlsberg ‘humility’ playbook. The brand has continued to use the crown icon, and that helped us maintain our belief in the quality of their product even when Carlsberg recently toned down their historical claim and indicated that they were “Probably NOT the best beer in the world” in line with more contemporary bottom-up cultural values of self-aware honesty and commercial and product integrity. Modesty of this kind is aligned with a culture which prioritises social mobility over class hierarchy, and enabled Carlsberg to simultaneously signal both its relevance to a changed cultural context AND its cherished brand equity.

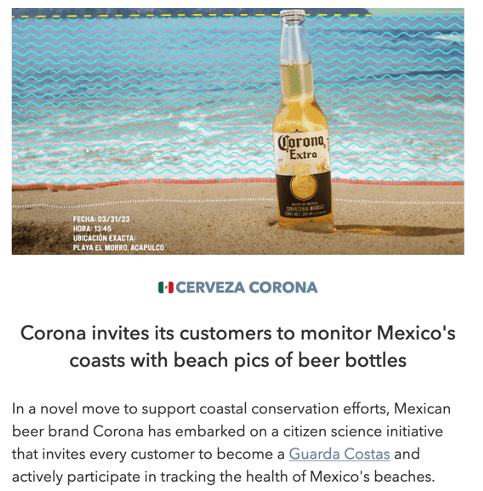

Another method, is to adopt a social conscience initiative which connects the brand to current consumer concerns and cultural needs. Corona, the Mexican made beer, whose name alludes to the most prominent of their distinctive brand assets – a crown – has recently developed a campaign inviting people to support coastal conservation efforts by helping to keep garbage off beaches ensuring their environmental health. In this way, Corona’s crown icon connotes the ‘leadership’ values associated with royalty, but transposes it into a mutually beneficial shared volunteering initiative, rather than connoting the expected hierarchical dominance.

Finally, employing a more conversational and comic peer to peer tone of voice can shift the brand away from the formality and seriousness associated with royalty and its often overly structured ‘pomp and circumstance’ events, activities, and clothing. While not a luxury brand, Crown Paints has created a careful balance between its crown icon signifying the quality of its product and the fun, energetic, irreverent and friendly tone of voice signifying its brand identity. In addition, the sunny and welcoming disposition is reinforced by the bright colours splashed across their website, which contrast with the formal and dark purples and burgundies traditionally associated with royalty. This combination of high quality product delivered by a down to earth brand allows the crown icon to act as a culturally meaningful guarantee to consumers, who are warmly invited to participate in a conversation with the brand, not asked to be deferential to an authority that Crown Paints doesn’t naturally have.

3 key takeaways for brands:

- Unless managed carefully, the ubiquity of crown icons used by both luxury AND value brands devalues their benefit as a way to signal high quality, and distinctiveness.

- ‘Crown’ icons employed by brands which once represented positive values of royal quality, leadership, authority, authenticity, elite luxury, and specialised mystical superiority are now increasingly associated with negative values of elitism, outdated detachment from ordinary people, and less relevant to the more meritocratic and inclusive contemporary social and cultural moment.

- By utilising 3 key methods, brands can maintain the equity of their crown icons but balance them with more contemporary socially relevant values: a) modesty b) social action initiatives c) peer-to-peer tone of voice and visuals.

Alex Gordon, CEO